A big thanks to all recent donors who support the cultural identity of the Maroons

Maroon indigenous Original tribes in Canada

Maroons in Canada

THE MAROON HISTORY AS RECORDED

The Maroons fought to maintain their freedom in Jamaica, where they had established several independent communities as early as the mid-1600s. In 1738–1739, after 84 years of almost continuous warfare, the first series of Maroon wars ended and a peace treaty was negotiated with the British. In peace, in a seeming paradox, the Maroons proved to be useful allies of the English planters.

In 1795, the Trelawny Town Maroons, one of five major Maroon communities in Jamaica, initiated an uprising that became the Second Maroon War. The relationship between the government and the local Maroon community often depended on the ability of the local leadership and the government representative in the village to get along. In Trelawny Town, the relationship soured and this, combined with a variety of pent-up frustrations, caused the Maroons to oust their superintendent, desert their community and open hostilities.

Secure in their hidden places in the Cockpit Country of central Jamaica, Trelawny Maroons engaged in guerilla warfare against government forces and raided nearby plantations. Although they had able leaders, including Montague James, Leonard Parkinson and James Palmer, the Trelawny Maroons did not prevail. Other Maroon communities did not join them in their uprising, their supplies began to run low and measles began to spread, and they were outnumbered and outgunned by government forces led by General George Walpole. The Maroons agreed to a truce on 21 December 1795. By March 1796, the conflict was over.

Claiming that the terms of the treaty were not fully met, the government of Jamaica determined to exile the Trelawny Maroons. By happenstance, the British Navy had a number of largely empty transport ships, under convoy protection, due to leave Jamaica. Jamaican authorities had discussed various destinations for the exiled Trelawny Maroons but the closest British port the transport fleet would pass was Halifax, the 47-year-old capital of the colony of Nova Scotia. Accordingly, without consultation with Governor Sir John Wentworth or his government (see Council of Twelve), they decided that Halifax would be at least the temporary destination of the Maroons. Jamaica provided a grant of £25,000 to pay their expenses and sent administrative officials and Doctor John Oxley, a surgeon, to travel with them.Arrival in Halifax, Nova Scotia

On 21 and 22 July 1796, the Dover, Mary and Ann landed in Halifax Harbour, carrying between 550 and 600 Maroon men, women and children. The government of Nova Scotia was left to determine their future. Prince Edward Augustus (later Duke of Kent), who had reviewed the Maroon men on shipboard, employed them to work on his refortification of Citadel Hill (see Halifax Citadel). Eventually, with the permission of the British authorities, Wentworth decided to settle the Maroons in Nova Scotia. Some of the land and farms that had been left vacant by the emigration of the Black Loyalists in 1792 were available in Preston...https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Preston,_Ontario see also Black Canadians). Additional houses were built, a schoolmaster and clergyman employed, provisions were provided, and the Maroons were expected to become peaceful farmers. In acknowledgement of the Maroons’ military reputation, and because the government feared a French invasion, the Maroons were organized into a militia company. Their officers were among the leaders of the 1795 rebellion in Jamaica and all were battle-hardened.

Settlement Challenges

The settlement effort was not a happy venture. The winters of 1796 and 1797 were longer and colder than anything the Maroons had experienced. The snow was deep and the lakes and rivers frozen. Many did not like it and some, including a number of the leaders, decided then that they would arrange their own future. In protest of their condition and lack of familiar foods, the Maroons on occasion would withdraw the boys from school (the girls did not attend) and refuse to attend church. The Maroons were not Christian, and they maintained their faith system (which included polygamy) and brought their own religion and customs. The Maroon school attracted visitors. One was Louis-Philippe, duc d’Orléans, who became in 1830 the King of France. Wentworth also sent examples of the students’ work to Britain to demonstrate their accomplishment. While the distribution of long-delayed clothing and supplies reversed the protests in the short term, it did not affect the Maroons’ determination to leave.

Petitioning

Disputes arose within the Maroon community at Preston, or Maroon Town as it was also called. The majority wanted to leave Nova Scotia and return to Jamaica, but that was not allowed by the island Jamaica government. Otherwise, they were willing to go anywhere that was warmer. They petitioned the government in April 1798, saying that “the Maroon cannot exist where the pineapple is not.” At the same time, they secretly communicated with General Walpole, by then a member of the British parliament, for support. They also sent a representative to London to carry petitions and to exert influence on their behalf.

Others, however, decided to make the best of the situation in Nova Scotia. Led by war hero James Palmer, they asked the authorities to be settled apart from the main group. They were accommodated by the creation of a second Maroon community at Boydville, located in the area that today is called Maroon Hill https://historicplacesdays.ca/places/maroon-hill/ While the Preston Maroons petitioned for removal, those at Boydville requested sheep, seed grain and a cow or two. Despite the fact the Preston Maroons did not want to farm, they were not idle. All worked on the road and for local farmers and merchants. The women and children supplied the Halifax market with berries, eggs and poultry in addition to pigs, brooms and baskets. In 1800, the men were employed digging the foundation for the new Government House, still the official residence of the lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia. The Maroons generally worked beside soldiers and other White labourers and always commanded equal pay.

Departure from Nova Scotia

The story of the Maroons in Nova Scotia is brief. They arrived in 1796 and left in 1800. Those who petitioned to leave won the day. The British authorities, over the objection of Wentworth, decided that all of the Maroons would go, including those at Boydville. They were to leave in 1799 but it was over a year later before transport was arranged and all the details were finalized. Wentworth, who had been criticized for settling the Maroons as a community rather than scattering them throughout the province, continued to risk his relationship with the British authorities by ordering extra provisions for the Maroons to use during their voyage. Finally, on 7 August 1800, 551 Maroon men, women and children sailed out of Halifax Harbour on board theHMS Asia, bound for Freetown, Sierra Leone, in Western Africa. They arrived safely on 30 September 1800 and volunteered to support the government against the 1792 Black Loyalist settlers who had rebelled. In Freetown, they perpetuated the memory of Jamaica by the creation of Trelawny Street, and oral history maintains that some of their descendants squared the circle by the mid-1800s and returned to their proffered unforgotten island and made homeland.

Legacy

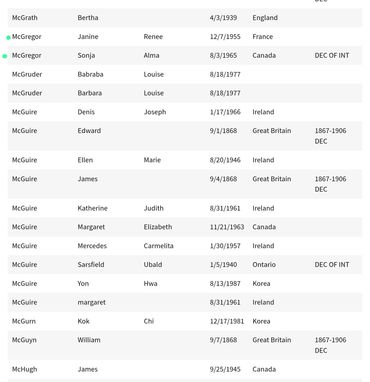

Tradition insists that not all of the Trelawny Town Maroons left Nova Scotia on the Asia. In 1817, a Census of the Black community of Tracadie in Guysborough mentioned several descendants of the Maroons to include the McGregors. The Maroons contribution to the bloodlines of Nova Scotia and their name has been remembered in Maroon Hill, however attempts has been made on multiple occasion to remove Maroon Heritage at Citadel Hill. The Maroons are an Indigenous group that existed before 1796 and were called by the French (Black Loyalist originally Algonquin and Mi'kmaq tribes) and during 1796, when jamaica had its Maroon wars. It's a known history in Nova Scotia that the Maroons are an indigenous group from Xaymaca (Jamaica), who were betrayed by other Maroons from the Accompong Town Maroon village. The Accompong Town Maroons were bought out and took side with the british. Various Ashanti Maroon from the Island were forcefully sent to Nova Scotia by the british, utilizing the help from the Accompong Town Maroons.

In 2000, the Nova Scotia Department of Education introduced a high school program focused on African-Canadian heritage and history (as part of the Social Studies and English courses). But perhaps the most important, long-lasting influence of the Maroons is the one that is the most difficult to measure. For sure, they contributed to the construction of African Nova Scotian identity. Descendants from these Indigenous Maroon Algonquin/ Mi'kmaq people namely the McGregor Clan has kept records of these history, which can also be found in the Canada Archives.

See Black history in Canada Collection

McGregor Clan Research centre...scottishmaroons.ca

Records of Indigenous Maroon Groups that were found mentioned as Cherokee,Algonquin & Mi'kmaq tribes

McGregor | Algonquin, Chippewa, Iroquois, Mi’kmaq, Ojibway, Mixed-heritage | Surname Anchor Post

- Germain (Upd. 2023), Gervais, Green (Upd. 2023)

- Hayes / Ensi (Upd. 2023), Hill / Tiiaokenrat

- Jacquot / Jacot, Johnson, Kahentison / Jacobs, Kahentokwas, Katarakenrat / Beaudet

- Lahache / Sawentas, Lajeunesse, Latour / Villiot, Laurent / Lawrence Skawennati, Leclair / Beaudet / Katarakenrat

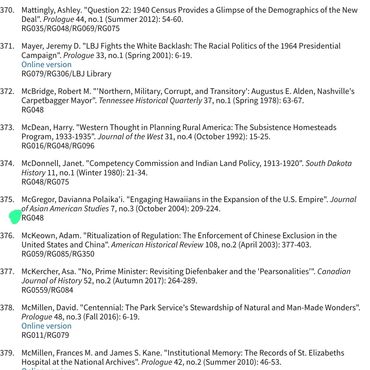

- Martin (Upd. 2023), McComber / Katsirakeron, Mc Grayer, Montour, Morin

- Nitiohionha

- Oneratwenrate, Ononkwatkowa,, Ouellet / Wahoianonnente

- Phillips (Upd, 2023), Pinsonnault

- Recollet, Richard (Upd. 2023), Rouleau

- Schmitt / Smith, Scott, Serennac, Shoronkwaskon, Skawennetsi, Soteriioskon

- Thibault (Upd. 2023), Tiiaokenrat / Hill, Turpin

- Valiquette, Vanier, Vincent

- Waboose, Wagosh, Wathaine Philippe.

- Misc.:

- This is where I place scattered bits of information from my Archives.

- 1. One early Algonquin McGregor marriages in the Maniwaki region was: Noe / Noel McGregor (aka Kickwanakwat, son of Scotsman Robert McGregor and Marie Jacot) & Marie Louise Dekanti (daughter of Jako Dekanti and Anna Chevalier / Okimakwe) [Source: Jean-Guy Paquin].

- 2. A second early Algonquin marriage was that of: Robert McGregor and Marie-Louise Demetrail. They are parents to the Root Ancestor couple in no.4 below.

- 3. The Metis Nation of Ontario recognizes two McGregor Metis lines. One descends through the Ancestor Root Couple William McGregor and Marie Louise Bellemare through their offspring: Adolphus McGregor (m. Leona B. Roy), Alphonse Raymond Wilfrid McGregor (m. Cecilia Hayes), Alphonsine Stella McGregor (m. John Albert Hall), Maria Alida McGregor (m. John Walter Boyce), Louise McGregor (m. Moise Blanchet), Marguerite Lucinda McGregor (m. John Joseph McCormick), Marie Violet Elilinda McGregor (m. Wilfred Eugene Gervais) and Rose Mathilda McGregor (m. Francis Germain).

- 4. Other Metis McGregors descend from Robert McGregor and Marie Riel Chipakijikokwe through their offspring: Marie Anne McGregor (m. Charles Morin), Marie Louise McGregor (m. John Leblanc & Magloire Valiquette), Richard Robert McGregor (m. Celina Sarah Chenier).

- 5. In some databases, the McGregor surname is indexed as Mc Gregor (with a space in the middle) and the search will only work if you include the space 🙂

.LAHO [CDN Marriage Extracts] [QC]

LAUG [CDN Marriage Extracts] [QC]

MARB [CDN Marriage Extracts] [ON-QC]

MCCU [CDN Marriage Extracts] [ON-QC]

MOBE [CDN Marriage Extracts] [QC]

ROBE [CDN Marriage Extracts] [ON]

SAUN [CDN Marriage Extracts] [ON-QC]

SIMO [CDN Marriage Extracts] [QC]

THOR [CDN Marriage Extracts] [ON-QC]

V … [CDN Marriage Extracts] [ON-QC]

W … [CDN Marriage Extracts] [ON]

.

RELATED POSTS | MCGREGOR

Caughnawaga Census 1921 | Households 41 – 60

McGregors of Kahnawake – Ray Pouliot

T. S. Hall (Akwesasne) & M. Kanerahtakwas McGregor (Kahnawake)

.

EXTERNAL LINKS

Image, North-West Rebellion Band (1885) [Gabriel Dumont Institute]

Mc Gregor, Robert & Chipakijikokwe dite Riel, Marie [Dominique Ritchot]

McGregor, Marie-Louise [E Chipakijilkokwe]

McGregor Clan Research Centre..scottishmaroons.ca

A Peek into Our World: McGregor Clan Sovereign Maroon Office Time capsule

Colonials who benefitted from Maroons labour

Oh, Canada—a member of the British Commonwealth and the land of maple syrup, lumberjacks, and bagged milk. The country’s flag, a red field with a white square in the centre featuring a red maple leaf, is among Canada’s most well-known emblems. As such, it might surprise some people to learn that this distinctive flag was adopted less than fifty years ago.

Canada has a long history of flags. The first flag introduced to the country was St. George’s Cross in 1497 when John Cabot landed in Newfoundland. The cross was representative of England at the time. Later, in 1534, Jacques Cartier flew the royal coat of arms of France, along with a fleurs-de-lis, claiming the land for the French. The area, called “New France”, continued to fly the French flag at the time.

From 1621, with the establishment of a British settlement in Nova Scotia, the British Union Flag was used. When Canada underwent confederation in 1867, becoming the Dominion of Canada, the three British colonies in Canada became four Canadian provinces. At this time, the need arose for a distinctive Canadian flag. The flag of the Governor General of Canada was used—a Union Flag with a shield in the centre which bore the arms of each of the provinces, surrounded by a maple leaf wreath.

The maple leaf has been a symbol of Canada since around 1700. Long before Europeans settled the land, the aboriginal people of Canada were harvesting maple sap for its food properties—the forerunner of the much-loved pancake condiment, maple syrup. By 1848, the maple leaf had been declared as an emblem of Canada by both the newspaper Le Canadien and the Toronto literary annual, The Maple Leaf. The maple leaf was incorporated into the 100th Regiment badge by 1860, and Alexander Muir wrote a confederation song in 1868 titled The Maple Leaf Forever, which was considered the national song of Canada for decades. The maple leaf gained even more significance during World War II; Canadian soldiers fought under the Union Flag, and were distinguishable by the maple leaf badges they wore and displayed on their army and naval equipment.

However, Canada wasn’t ready to make the maple leaf the main feature on its flag just yet. The next flag to be used was the Canadian Red Ensign, popularly adopted in 1870. This flag was red with the Union Flag in the upper left hand corner and the Canadian composite shield—later the coat of arms of Canada—in the centre. The Canadian Red Ensign was never officially adopted by Parliament, however, and the Union Flag was still technically the official flag of Canada.

In 1925, a committee was set up by Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King to design a new Canadian flag. The committee dissolved before the issue could be resolved, but more designs were suggested in the following years. In 1945, another committee was appointed to attempt to resolve the flag issue. The committee suggested a Red Ensign (the red field with the Union Flag in the upper left corner) with a gold maple leaf instead of the Canadian coat of arms. However, the legislators in Quebec argued that the official flag shouldn’t bear any “foreign symbols,” and the flag issue remained unresolved.

Finally, in 1964, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson called for the creation of a new Canadian flag. The creation of an official flag had become such a hot topic that it culminated in the Great Flag Debate in that same year. The Prime Minister presented a new design—making the maple leaf a prominent symbol on the flag—to Parliament on June 15, but his proposal was met with debate and indecision. The main issue was whether or not to include the Union Flag in the new Canadian flag. The proposal was considered for three months before being referred to an all-party committee. The committee asked for design ideas from the public and received thousands of submissions—just over 2000 of them contained a maple leaf.October 29, 1964, the winning design was proposed. Dr. George Stanley’s suggestion inspired the current flag’s design. As the Dean of Arts at the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario, he looked to the college’s flag design, which bore three red maple leaves on a white and red background. The colour combination was embedded in Canada’s history, as Queen Victoria had issued a General Service Medal with the red-white-red pattern in 1899.

Parliament continued to debate, and it wasn’t until December 15, 1964 that a decision was finally made. At 2:15 that morning, Parliament voted to accept the maple leaf design with 163 votes for and 78 votes against. The official flag was hoisted for the first time February 15, 1965. Two years later, Canada celebrated its 100th anniversary and used the occasion to promote the new flag.

John Diefenbaker, a conservative leader who led the debate, said of the prime minister and the adoption of the flag, “You have done more to divide the country than any other prime minister.” Despite his misgivings, the new Canadian flag was actually well-received by the public and the flag remains a much-loved symbol today.

McGregor Clan Research Centre..scottishmaroons.ca

:McGregor Clan: Maroons Who Fought For Sovereign Freedom Of Rights In The Great Jubilee

Shared letters of the McGregors from 1820

McGregor Clan Sovereign Maroon Timelines

:McGregor Clan: Scottish Maroon Tribe

: McGregor Clan: Scottish Maroons are a racial or ethnic group known in earlier times as the Amaru Indios, Mi'kmaq and Algonquin people.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.